A novel approach to the treatement of low back pain?

A powerpoint presentation! Click on slide to advance through a quick slideshow! ie., 2 slides in 2 minutes!

It is estimated that 40-90% of individuals will experience back pain during their lifetime (Scott et al., 2010).

Definition: Any discomfort or pain below the ribcage and above the inferior gluteal fold, in addition leg pain can be present or absent (Van Tulder et al., 2006)

WHY BOX SQUAT?

Why Box Squat?

By: Ab Campbell MSc Kinesiology

Introduction

Although a book could be written on box squats; I will keep this somewhat brief. Box squatting has multiple utility in various contexts from beginners, intermediate, and to the elite. Box squat’s benefits can be applied to the general population, both raw & geared powerlifting, injury prevention, rehabilitation, and athletics. So first let’s examine the history of box squatting; followed by a “how to” guide to the box squat, the mechanisms of the box squat, its application in various contexts, a research-based narrative review and finally a take home message/Conclusion

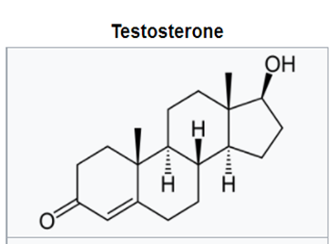

Testosterone’s Modulation of Muscular Strength

Testosterone (T) is generally associated with masculinizing characteristics such as sex drive, bone mass, muscle mass, body hair growth, fat distribution, and hematocrit levels (Leon et al., 2021). However, less commonly associated with testosterone is its role in emotion, social behavior, development of brain structures, and neural protection (Derntl at el., 2009; Filová et al., 2013; Montoya., 2012; Oki et al., 2015). Although, testosterone and its modulation of muscular strength has been debated in the academic community for over five decades (Bhasin et al., 2001). However, testosterone’s influence on muscular strength is unequivocal (Bhasin et al., 1996; Bhasin et al., 2001; Blazevich et al., 2001; Giorgi et al., 1999; Kvorning et al., 2006; Storer et al., 2003). It is clearly demonstrated that testosterone deficiency results in low muscle mass and consequently decreases in functional strength (Grinspoon et al., 1996; Mauras et al., 1998). However, upon the restoration of testosterone to normal biological values (264 to 916 ng/dl or 9.16 nmol/l to 31.7 nmol/l) (Travison et al., 2017) subsequent losses in muscle mass and strength are restored in both the young and elderly male hypogonadal populations (Morley et al., 1993; Urban et al., 1995; Bhasin et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2000). However, the administration of supraphysiological exogenous testosterone (elevating serum levels of T > 916 ng/dl or 31.7 nmol/l) and its derivatives Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids (AAS) to increase muscle mass and strength has been widely criticized by the academic community citing the lack of evidence (Bhasin et al., 2001). This is despite AAS’ ubiquitous use among athletes for multiple decades dating as far back as to the 1936 Olympics (Bhasin et al., 2001; Yesalis et al., 2002). The lack of association between testosterone/AAS and muscular strength is mostly due to poor methodology, inadequate dosing protocols, inaccurate evaluative methods, and lack of control of confounding variables which resulted in inconclusive or contradictory research findings (Bhasin et al., 2001). Therefore, the purpose of this review is to examine the evidence concerning testosterone’s indispensable role in muscular strength adaptations and to elucidate the mechanistic link between testosterone and strength. This will be accomplished by examining and critically analyzing the current body of literature on this topic.

Foam rolling’s effect on athletic performance and injury risk reduction

Foam rolling (FR) has become a popular exercise “recovery tool” used by athletes in recent years. It has also been proposed that FR can improve athletic performance and reduce injury (Wiewelhove et al., 2019). Advocates claim FR alleviates muscle soreness, reduces joint stress, improves; range of motion, muscular imbalances, and neuromuscular efficiency (Macdonald et al., 2014). However, there is little consensus on FR protocols, effectiveness, or physiological mechanisms (Hendricks et al., 2020; Wiewelhove et al., 2019). Therefore, the purpose of this review is to evaluate and summarize the relevant literature on the effectiveness of FR on athletic performance and injury risk reduction. Secondly, based upon the evidence FR protocols (pre- vs. post- exercise, duration, and frequency) and physiological mechanisms will be discussed to highlight clinically relevant recommendations for patients, athletes, and clinicians.

Written Grant ProposaL: Caffeine and Accommodating Resistance Effect on The Rate of Force Development:A 12-Week Training Intervention

Caffeine is one of the commonly most used performance aids in athletes. However, caffeine’s ergogenic effects on short-intense, strength, sprint, and power exercise remain unclear (Sökmen et al., 2008). Bazzucchi et al., (2011) demonstrated caffeine’s effectiveness on the rate of force development. The rate of force development is a measure of explosive-strength, it is the ability to produce force or torque during a rapid voluntary contraction from a resting state (Maffiuletti et al., 2016). RFD is important in both sport performance and for explosive-strength athletes (Maffiuletti et al., 2016). However, RFD (reduction) also has broader implications in association with functional daily living tasks in the elderly, in the context of rehabilitation interventions, and various pathologies (Buckthorpe & Roi., 2019; Maffiuletti et al., 2016).

Can Caffeine improve strength ?

A powerpoint presentation! Click on slide to advance through slideshow.

CAN DEADLIFTS IMPROVE LOW BACK PAIN?

The prevalence of low back pain has resulted in a challenge to medical systems internationally and is also the leading cause of years lived with a disability (James et al., 2018). Low back pain is one of the most financially burdensome of all musculoskeletal disorders (Bell & Burnett, 2009). It is estimated that 40-90% of individuals will experience back pain during their lifetime (Scott et al., 2010). Van Tulder and colleagues (2006) define low back pain as discomfort or pain below the ribcage and above the inferior gluteal fold, in addition leg pain can be present or absent. In this literature review I will examine the neuromusculoskeletal training improvements asserted by the barbell deadlift in low back pain rehabilitation interventions

Back pain is classified by health care professionals as chronic; > 12 weeks, sub-acute; between six-twelve weeks of pain and acute when symptoms last < 6 weeks. (Van Tulder et al., 2006). Examination of low back pain presents a difficult task for health care professionals as there is an absence in validity of diagnostic tests to determine what musculoskeletal structures are generating the pain (Holmberg et al., 2012). As a result, 85% percent of low back pain diagnosis are classified as non-specific chronic low back pain based upon radiologic findings even when associated pathology is determined (O’Sullivan., 2005).

Low back pain is a complex and multi-factorial biopsychosocial musculoskeletal disorder resulting in difficulty diagnosing it clinically and therefore finding treatment interventions (O’Sullivan., 2005). Pathological analysis of persistent low back pain in patients’ origin of pain can be attributed to following anatomical structures; 39% intervertebral discs, 15-40% joint facets and 30 % sacroiliac joints (Manchikanti et al., 2001). Other neuromuscular etiological causes can be attributed to; maladaptive activation of stabilizing structure of the lower back due to spinal disturbances (Hodges & Richardson, 1999), sub-optimal movement patterns causing overload of the lumbar spine (Michaelson et al., 2016), hypotrophy of type two muscle fibers and back extensor musculature in chronic low back conditions (Holmberg et al., 2012), and altered alignment resulting in tissue stress and altered muscle activation patterns (Aasa et al., 2015). Additionally, associations have been documented between low back pain and muscular weaknesses of the musculature of the trunk (Hultman et al., 1993) and weakness of the lower extremities (de Souza., 2019).

EVER WONDER WHAT HAPPENS TO FOOD AFTER WE EAT IT?

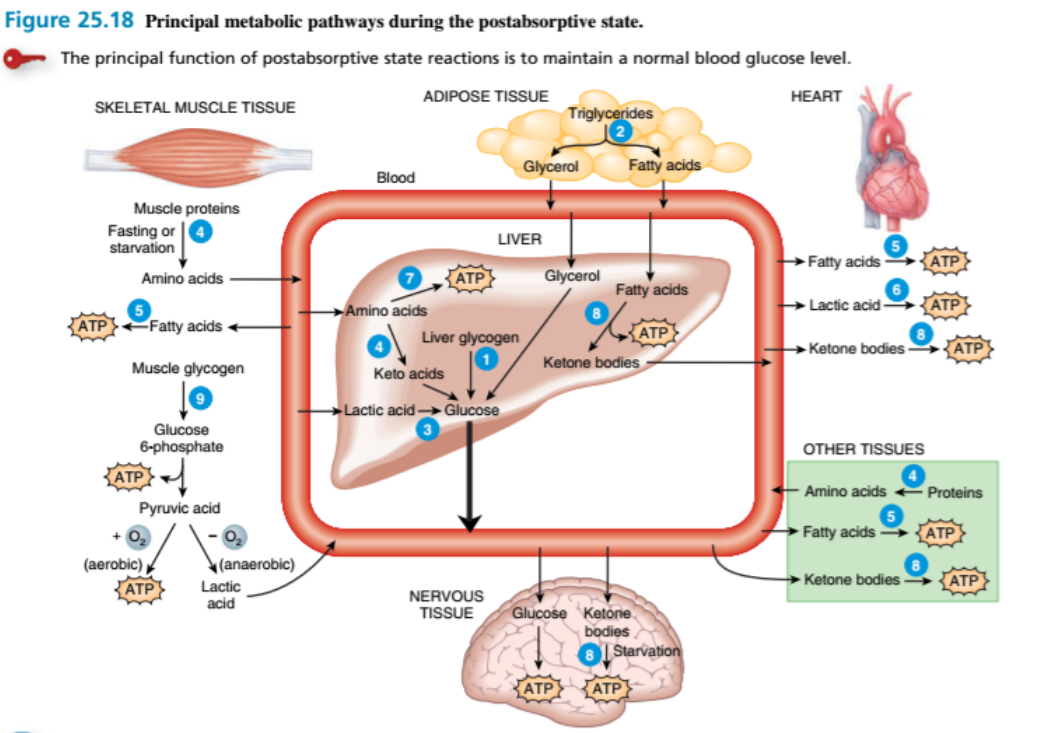

After digested nutrients enter the blood via absorption in the small intestine (mechanisms not covered in article) in the form of amino acids, glucose and triglycerides (carried in chylomicrons) oxidation of glucose for ATP (cellular energy) production occurs in most body cells, while any excess “fuel” molecules are stored in hepatocytes (liver cells), adipocytes (fat cells) and skeletal muscle fibers for future use between meals. This process is known as the absorptive state (mechanisms beyond scope of article). How then is energy maintained or more specifically how is blood glucose stabilized long after a meal (4 hours) after all absorption of nutrients is almost completed in the small intestine?

Blood glucose homeostasis is extremely important for the body’s cells and especially important for the nervous system and red blood cells.

This is known as Postabsorptive state, and the following mechanisms help prevent hypoglycemia (ie., blood glucose below 3.9 – 6.1 mmol/liter) in otherwise healthy individuals. During this postabsorptive state glucose is both conserved and produced to maintain normal blood glucose levels. For example, the liver cells (Hepatocytes) produce glucose and release molecules into the bloodstream. In contrast, other body cells switch from glucose to alternate fuels for the production of cellular energy (ATP) for glucose conservation.

Mechanistically, the major postabsorptive reactions that produce glucose and glucose conservation are indicated below (see diagram, not included are the hormonal regulators ie., “ant-insulin” hormones if interested further, please refer to chart below. These hormones aid in the increase/conservation of glucose/ATP)

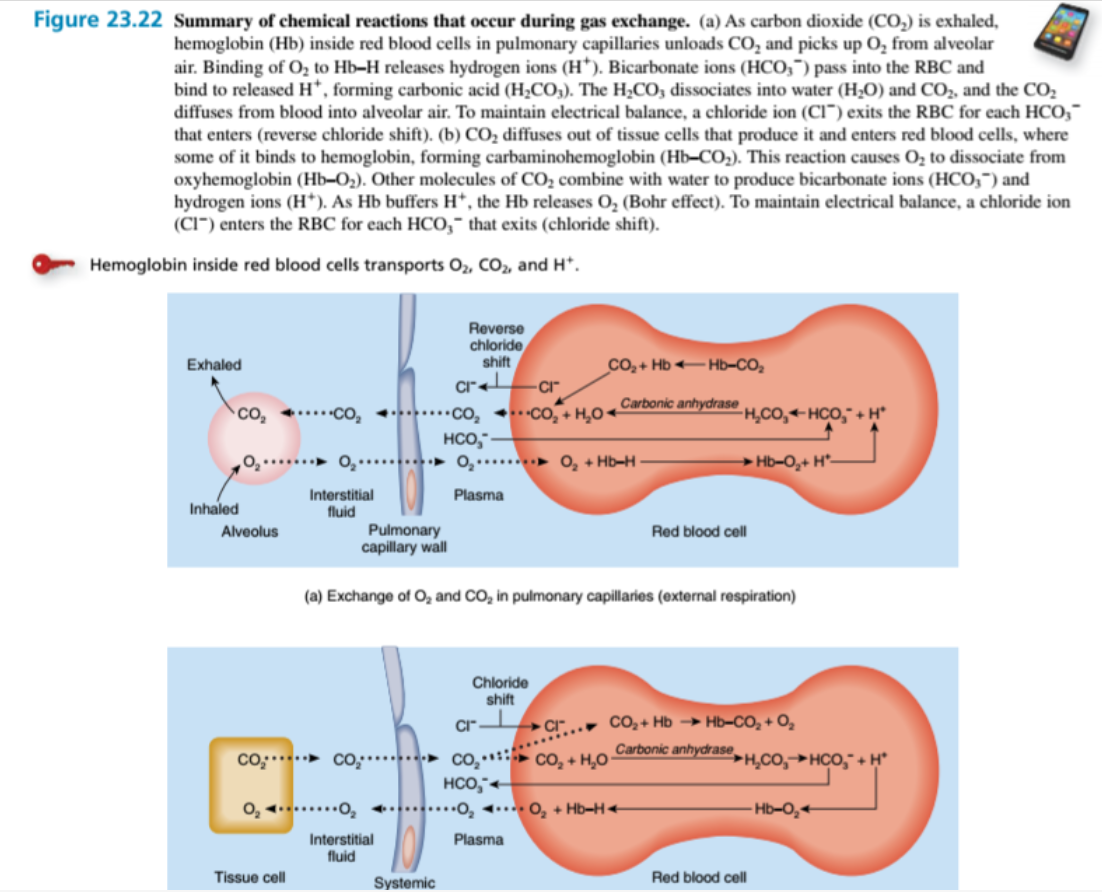

WE ALL KNOW WE INHALE OXYGEN AND EXHALE CARBON DIOXIDE, BUT WHY? AND HOW IS THIS INVOLVED IN MUSCLE CONTRACTION?

Exercise results in the diffusion of O2 from the blood into metabolically active cells, such as contracting skeletal muscle fibers. Active cells use more O2 for ATP production via metabolic intermediate Acetyl-Coa derived from glucose, fatty acids, or amino acids and ketone bodies.

The rate of pulmonary and systemic gas exchange depends on several factors in sum;

A)Partial pressure difference of the gases

B)Surface area available for gas exchange.

C)Diffusion distance.

D) Molecular weight and solubility of the gases.

Without getting too technical; mechanistically on a chemical level the processes in which carbon dioxide and oxygen are transported is described below (see figure 23.2 for biochemical details; Ultimately, we exhale CO2 transported from tissue cells and provide our working cells with O2. Note that CO2 transportation occurs in the following ways 7% dissolved in blood plasma, 23% as Hb–CO2 (carbaminohemoglobin) 70% as HCO3- (bicarbonate ions) Transport of O2 is dissolved in blood plasma (1.5%) and 98.5% as Hb–O2 (oxyhemoglobin)